New Labor Market Policies Will Be Needed for the Era of Artificial Intelligence

New Labor Market Policies Will Be Needed for the Era of Artificial Intelligence.

Several recent posts have explored different aspects of the scale and scope of social, economic, and political disruption that may overtake the world’s most advanced, urbanized, and prosperous nations because of the rapid evolution of today’s version of artificial intelligence (AI) tools.

Analysts differ about many key aspects of how AI will affect society. First, they differ about the timing of AI’s evolutionary technological breakthroughs. Prominent labor market economists, for example, see today’s generation of domain-specific tools as the principal source of disruptions for the next decade or so.

The best analogy for what to expect, they assert, is our previous experience with office automation like desktop and laptop personal computers equipped with “killer apps” like spreadsheets and word processers. These revolutionary technologies took more than a decade to transform office work for hundreds of thousands of private and public organizations around the world. Millions of administrative support jobs were eliminated over time, but the process was slow enough for most organizations and workers to adjust through changing job descriptions and allowing job attrition rates to absorb a large percentage of the job losses.

Other analysts, including many technologists and technology entrepreneurs, see today’s AI tools as a temporary stage that will be swept away quickly by vastly more powerful General Artificial Intelligence (GAI) tools.

If the technologists are correct, the timespan for disruption could be a few years, not decades. Even if GAI tools are slower to materialize than they predict, technologists still assert that today’s AI tools will diffuse much faster than earlier technologies because the financial benefits of today’s AI tools are just too big to ignore.

Organizational cultures, especially in the private sector, they assert, are much more willing to adopt new technologies today than they were twenty or thirty years ago. The “move fast and break things” culture of Silicon Valley has spread throughout the global economy. Slow adopters of today’s AI tools will face punishing competitive forces. Consequently, AI tools are expected to begin replacing human employees quickly.

But who will AI tools replace? This question raises another aspect of AI disruption that analysts disagree about: how will AI disrupt the occupational hierarchy within private and public organizations?

Labor market economists foresee a process that is largely bottom-up. They argue that today’s AI tools will restructure job descriptions and reduce job counts among entry-level and lower skilled office occupations. This process will impede the upcoming generation of college graduates by making it more difficult to get entry-level jobs, and by limiting opportunities for upward career mobility.

Technologists, on the other hand, foresee a process that also contains important top-down elements. Even today’s AI tools, they assert, have great capacity to integrate large amounts of domain-specific data into problem-solving algorithms that learn quickly how to model the consequences of alternative approaches in evolutionary environments. These skills match the job descriptions of mid-level and even some senior-level executives. The top-down element of job disruption would become much more pronounced as soon as GAI breakthroughs occur.

Personally, I find the arguments put forth by the technologists more convincing than those offered by the labor market economists. Yet even if AI disruptions radiate through the global economy at the slower pace predicted by the labor market economists, the consequences will require profound changes to the different social, economic, and political institutions that different nations have relied on to achieve sustainable distributions of income within their own contemporary systems of industrial social relations.

Financial capital is the greatest source of social authority in all industrial societies. Social, economic, and political institutions evolve according to different models of who controls financial capital, and how that capital can be expanded through economic development.

In the case of the U.S., most capital has always been held by private actors (individuals, families, and corporations). The last time the U.S. re-engineered those social, economic, and political institutions in fundamental ways was the period between the Great Depression of the 1930s and the advent of the Great Society programs of the 1960s.

The reforms of that period shifted control of a large portion of financial capital (through taxes and regulations) to an alphabet-soup collection of public agencies, mostly controlled by the U.S. federal government. The resulting increase in governmental power was used to dramatically increase the proportion of GDP that went to unionized and non-unionized employees. Financial benefits included higher hourly wages as well as more generous non-wage benefits for health care, retirement (social security and private pensions), unemployment, occupational safety, and other initiatives.

These reforms spilled over broadly across the economy to improve wages for salaried employees as well, even though they were not the principal target.[i] Hundreds of specific additions, subtractions, reforms, and other changes have occurred in different waves of reform to these “New Deal,” “Fair Deal,” and “Great Society” initiatives. Yet despite continual changes, the system itself has endured. Wages and salaries earned by all categories of employees, most of whom work in the private sector, accounted for $10.5 trillion in household income in the U.S. in 2022.

The emergence of AI, whether quickly or gradually, will undermine the core structure of the U.S. system, (and all others as well). Although previous general-purpose technologies have caused severe disruptions to labor markets by making many occupations obsolete, they have also created more jobs over time in new occupations than they destroyed. And the new occupations typically pay higher wages & salaries than the old ones. The net has always increased the amount of wage & salary income earned by U.S. households.

This is not likely to happen with AI because AI does not create new occupations. As far as we can tell, AI profoundly reduces the proportion of human knowledge skills needed to expand the GDP. The powerful logic that compels industrial societies to expand the value of financial capital through production will continue. Yet that logic will need fewer and fewer people to achieve this penultimate goal. Consequently, less of each year’s expanding GDP will be paid out to households in the form of wages and salaries. More will be retained by corporations and/or paid out to shareholders through dividends.

The loss of household income will affect high, middle, and low-income households although the proportional loss will increase as household income increases. Losses will cut across most sectors since knowledge-intensive occupations exist in all industries. And losses will not be concentrated in a subset of sub-national regions and/or metropolitan areas. Cities may experience the greatest losses since knowledge-workers tend to concentrate in urban areas, but losses will be ubiquitous.

Decreasing income taxes and payroll taxes will undermine the financial stability of the twentieth-century labor market system that was created to spread prosperity more broadly. Indeed, the American system of industrial social relations may experience a crisis that will exceed the “crisis of the old order” that culminated in the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Yet the financial capacity to implement major new reforms to address the coming 21st century crisis may not be as restricted as the capacity that reformers struggled with in the 1930s.

AI tools, especially GAI tools, bring with them the prospect of enormous new levels of GDP growth and corporate profitability. New ways must be found to tap into that fast-growing GDP to provide income security and other benefits for tens of millions of U.S. households who will face potentially catastrophic income losses that will not likely be replaced by new jobs. In addition, we still need to provide upward mobility for those who never experienced the full benefits of the current system.

Among the benefits that will be needed are:

· An expanded version of unemployment insurance that can act as a form of career insurance to compensate skilled employees whose skills are provided more efficiently by AI;

· Some form of universal income support for all adults since the opportunities for earned income will be diminished broadly;

· Some form of financial support for lifelong learning for all adults, to maximize opportunities for work in new fields and to maximize human fulfillment for those who may not find new paid employment;

· Universal access to health care and long-term retirement income benefits that are no longer connected to each individual’s earned income.

It is difficult to imagine any alternative other than introducing new forms of corporate taxation and payroll taxes, along with a host of new tax incentives to encourage specific corporate behaviors to minimize the scale and scope of job losses associated with diffusing AI into the economy.

Specific tax rates and incentives are beyond the scope of this essay. But it is worth noting that if new AI tools and/or GAI tools create higher annual rates of growth in GDP, corporate revenues, and corporate profits, there should be opportunities to re-engineer the system to increase the proportion of growth that accrues to government through taxes while still ensuring that returns to private capital still increase substantially.

Some estimated data from Fiscal Year 2023 can inform our thinking. In that year, the Fortune 1000 publicly traded corporations based in the U.S. had total revenues of about $20.2 trillion dollars. That amount corresponds to about 75 percent of 2023 U.S. GDP. The official corporate tax rate for profits in 2023 was 21 percent. Yet a reasonable estimate of the federal taxes actually paid by the Fortune 1000 companies is less than $180 billion, which is less than 1 percent of their total revenue.

Profits and revenues, of course, are not comparable measures. Yet these numbers suggest the scale of privately controlled financial capital that could be subjected to some new forms of taxation. These numbers could increase substantially if AI tools and/or GAI tools create high annual growth rates in both revenues and profits. Trillions of dollars could be reassigned to new types of governmental benefits for households while still providing rapid growth in financial returns to private owners of financial capital.

Any realistic assessment of the political feasibility of this scale of re-engineering social and economic institutions within American culture would surely conclude that these ideas verge on irrational utopian thinking. After all, American politics has been dominated by tax cuts and benefit reductions for at least a generation.

Yet American culture is flexible and pragmatic. And the scale of social, economic, and political trauma that might lay ahead – whether in the next few years or the next two decades – is enormous.

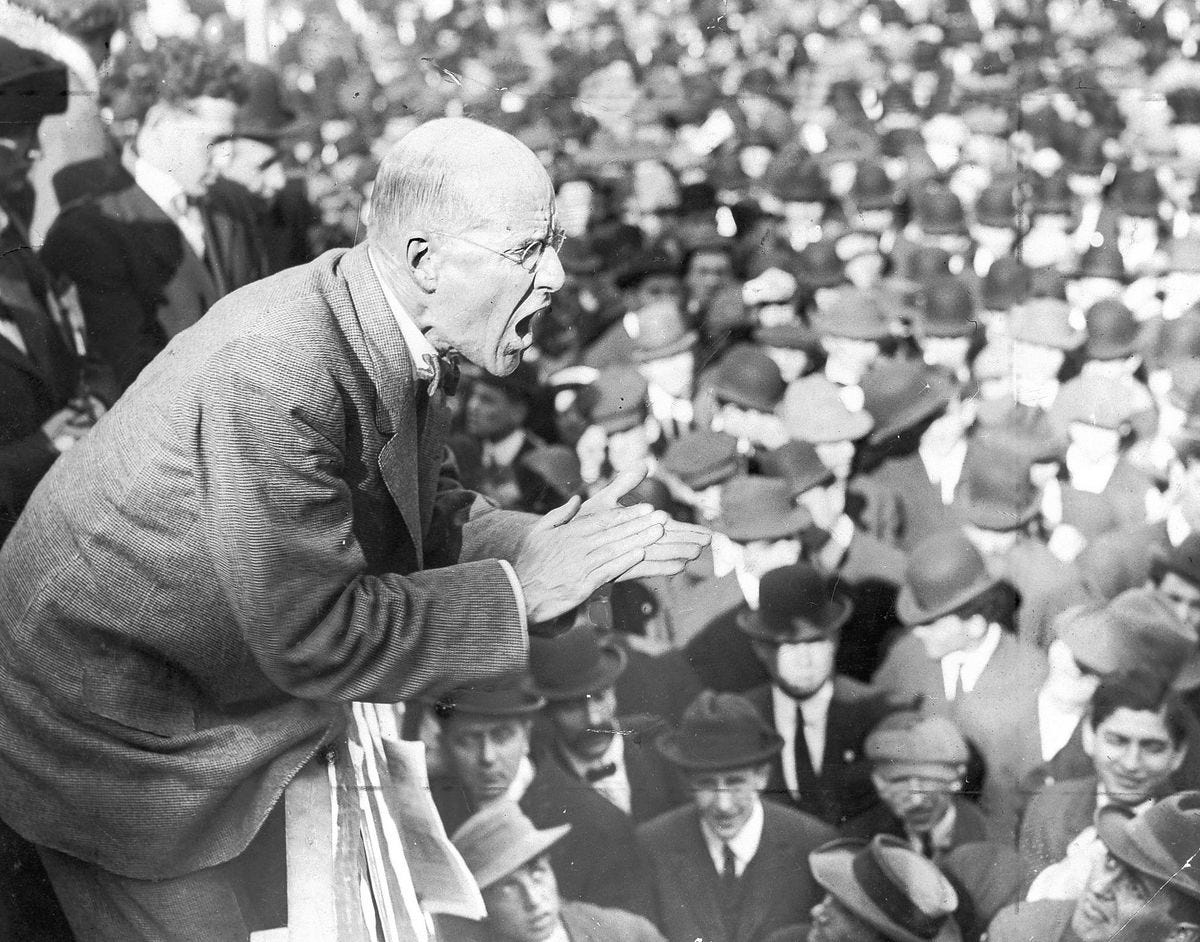

If American history can help inform our imaginations, it is very useful to recall that almost every one of the core elements of fundamental labor market and tax reforms that were put in place by Democrats and Republicans alike in the mid-to-late 20th century were central elements of the radical political platform pushed by Eugene Debs (1855-1926).

Debs was a founding member of the radial Industrial Workers of the World and he ran for President five times as the candidate of the Socialist Party of America. Indeed, during his final run for the Presidency in 1920 Debs earned only 3.4 percent of the national vote while he was still in jail for sedition because he spoke so eloquently against U.S. involvement in World War One.

Debs died three years before the stock market crash of October 1929. Yet his radical political agenda for the U.S. was gradually rebranded by pragmatic American politicians and became the conservative framework for eventual reforms that facilitated the ongoing successful evolution of America’s system of industrial social relations.

Bob Gleeson

IMPORTANT PROGRAMING NOTE

Substack now provides easy tools that encourage writers to add podcasts to their sites. Ever since Bill Bowen and I started this weekly post, readers have encouraged us to experiment with podcasting in addition to writing.

Consequently, we are happy (and nervous!) to announce our first podcast!

We previously scheduled our first livestream for TODAY (May 6, 2025) at 11am to Noon Eastern Daylight Time. BUT WE NEED TO RESCHEDULE THE EVENT TO BEGIN AT 4PM INSTEAD OF 11AM.

The podcast will be recorded and posted on the site, so it will not be necessary to join the livestream. We look forward to hearing your feedback!

[i] The distinction between “exempt” and “non-exempt” employees is still a major factor within the American system.